Translate this page into:

Robert Willan (1757–1812): An enigma in dermatology

*Corresponding author: Mohnish Sekar, Department of Dermatology, Karpaga Vinayaga Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Chengalpattu, Tamil Nadu, India. mohnishsekar@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sekar M, KavyaDeepu RM. Robert Willan (1757– 1812): An enigma in dermatology. CosmoDerma. 2025;5:7. doi: 10.25259/CSDM_199_2024

INTRODUCTION

Robert Willan was a beacon of faith, hope, and light to the underprivileged and slum dwellers of London in the 18th century. His dedication and sacrifice benefitted the more commons and paved the way for the definition and classification of cutaneous lesions, making dermatology a distinct subject in medical science. His sharp observations and reserved terminology for certain skin disorders have earned him the title “Father of Modern Dermatology.”

FORMATIVE YEARS

Robert Willan [Figure 1] came into this world on November 12, 1757, in the northwest corner of Yorkshire, at the Hill, in Marthwaite, not far from Sedbergh. His birthplace, a charming 18th-century farmhouse, and the surrounding countryside remain primarily unchanged since Willan’s day.[1,2]

- Portrait of Robert Willan. Image credit: Photograph by Cooper. This image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

FAMILY

Robert Willan senior, his father, was also a doctor with a stellar medical reputation and significant practice. Robert was the youngest offspring of the sixth generation of Willans, who had resided at Marthwaite since the mid-seventeenth century. Robert Willan wed Mary De Beaufre Scott, a physician’s widow, in the springtime of 1801. They had three children together: Two stepdaughters and a son named Richard. Mrs. Willan outlived her husband by a few years. Robert and his sibling Richard maintained a very close family bond.[2]

PERSONAL AND SOCIAL TRAITS

Despite being meticulous in his work, he was a sensitive individual who did not respond favorably to criticism or suggestions. He consistently demonstrated a keen interest in youth and their education. He was non-alcoholic and despised gambling. In his vocation, he was cherished to an exceptional degree: Modest, calming, empathetic, and consistently attentive to the well-being of his patients. He was genuinely truthful and notably devoid of any form of deceitful trickery.[2]

ELEMENTARY TRAINING

A brief walk down the hill to the church leads to the 18th-century schoolhouse, which now serves as the school library. This school was regarded to be among the best in the northern territory of England, and Willan attended it. He was a brilliant mathematician and a renowned classics scholar. Regarding school and its traditions, Willan had nothing but praise and affection.[2]

RESIDENCY

Willan attended the University of Edinburgh, considered among the premier medical schools of the era, from 1777 to 1780. It was profoundly influenced by the concepts developed by the Leiden School of Medicine. The Physical Society and the Royal Medical Society were two scientific societies that Willan was an official member of while he was a student in Edinburgh. He obtained his MD in 1780 with his dissertation “On Inflammation of the Liver.”[3] The thesis was composed and testified in Latin.[2]

LIFE AT EDINBURGH

Many well-known scholars were with him in Edinburgh, including Alexander Munro, John Brown (the founder of Brownian theory), Francis Home (the first person to record croup, which was later identified as diphtheria), and John Hope (a professor of botany) as well as exceptional students such as Benjamin Bell (the most renowned among Edinburgh’s scientific surgeons, who first described gonorrhea and lues in 1793) and John Bell.[3]

THE AGE OF REASON

Willan did not work in a renowned hospital due to his Quaker background, as only those from the Church of England were permitted to attend the established schools.[3] Willan’s professional contributions at the Carey Street Dispensary in London from 1783 to 1803 involved collaboration with graduates from Edinburgh University, notably Thomas Bateman, Richard Bright, and Thomas Addison. All were particularly intrigued by cutaneous diseases; nevertheless, the last two ultimately redirected their efforts toward distinct medical fields, achieving global recognition for their contributions to kidney and adrenal gland research, respectively.[4]

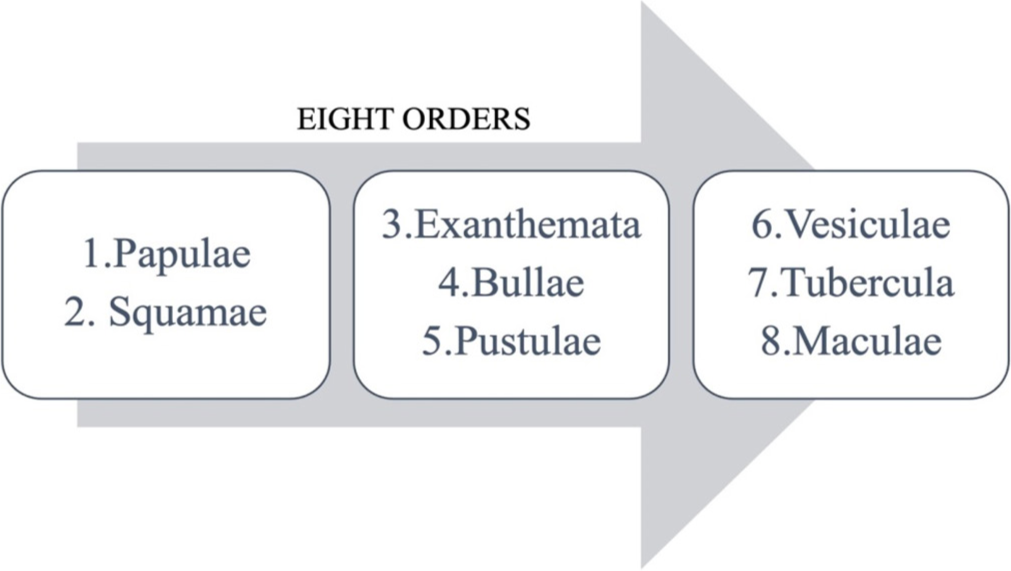

During the second part of the 18th century, the number of dispensaries in London experienced a consistent rise; for example, there was a single dispensary in 1769, whereas by 1800, this number had escalated to fourteen. Over the latter half, London experienced a rise in its population, predominantly composed of low-income individuals facing health issues, required dispensaries to provide healthcare services.[3] Willan spent a large portion of his time as a physician helping the underprivileged and disenfranchised people living in London slums in the 18th century. Hospitals in London during this period primarily catered to the affluent. As a result, dispensaries became the main source of medical care for London’s poor and ill. During his tenure at the Carey Street Dispensary, Willan cultivated an interest in dermatological illnesses.[5] He was the founding individual to acknowledge the significance of drawing in depicting skin ailments and the first physician to endeavor to establish a categorization system for cutaneous disorders, principally grounded upon the morphological characteristics of dermatologic conditions. His classification system had eight orders [Figure 2].[2,5]

- Willan’s classification of morphology.

Willan favored the broad efforts of Linnaeus, who advocated for classifying plants based on a singular and readily observable trait.[6] The Willanist theory classified cutaneous disorders according to the occurrence of fundamental lesions, regardless of the full course of the clinical process, in line with the botanical basis that groups plants according to common visible characteristics. Dermatologists also divided each order (papules, vesicles, bullae, etc.) into genera and species, just like botanists do. Papules were divided into two genera: Lichen and Strophulus. Five species of lichen were identified: tropicus, pilaris, agrius, lividus, and lichen simplex.[5,6]

In 1808, Willan wrote On Cutaneous Diseases, Volume 1, which provided a comprehensive account of his initial four classifications: Papulae, squamae, exanthemata, and bullae. This project also includes intricate illustrations of plates derived from watercolor renderings.[5] He authored the inaugural atlas of skin diseases, which included colored illustrations.[3] In dermatology, Robert has made important contributions. He was the first to accurately describe erythema infectiosum, cutaneous tuberculosis (Willan’s lupus), erythema nodosum, ichthyosis hystrix, lesions of herpes simplex and herpes zoster, molluscum fibrosum, tinea capitis, Schoenlein–Henoch purpura, acne rosacea, and senile pruritus (Willan’s itch).[3,4] Willan distinguished between prurigo mitis and prurigo formicans, two less severe but more troublesome forms of prurigo characterized by constant scratching. He highlighted hypersensitive reactions to insects, the feeling of crawling insects, and a possible connection to underlying constitutive disease. This is still true, but the internal sulfur-implementation therapy he suggested is now merely historical. His depiction of psoriasis is commendable, yet the assertion that each recurrence was preceded by unbearable itching lacks substantiation. Although he might not have been the first to characterize psoriasis, he was certainly the first to offer a thorough medical explanation of the ailment, calling it lepra graecorum and recommending that tar be applied locally to treat it. He found that the disease recurred more frequently in the spring and fall when exposed to cold and wetness. For many years, psoriasis was erroneously referred to as Willan’s leprosy. Crissey and Parish,[7] followed by Happle and Holubar,[8] introduced the term “Willan eye” to describe a unique visual acuity in dermatological conditions, a blending designation [Table 1].[3-6]

| Period | Attainments |

|---|---|

| 1785 | Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians |

| 1789 | Member of the London Medical Society |

| 1790 | Fothergillian medal |

| 1791 | Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries |

| 1798–1808 |

|

LAURELS AND ACCOLADES

On March 21, 1785, he enrolled in the Royal College of Physicians. He was elected to the London Medical Society in 1789. In 1790, he received the Fothergillian medal, a rare accolade for portraying cutaneous illness. Willan was made a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1791. This was done in appreciation of his long-standing interest in folklore and events belonging to the antiquarian community [Table 1].[2]

EXTRACURRICULAR APTITUDE

Willan was a master, even in the fields of philologist and antiquarian. He penned a piece titled “Lustration by Need Fire.” The book was shelved. He wrote extensively about how the weather affected different illnesses and published his findings in the “Meteorological Journal.” When it came to Jenner and the idea of vaccination, Willan was a staunch advocate. Among the first to do so, he highlighted the role of occupational and environmental hazards in developing pulmonary tuberculosis and other lung diseases.[2]

ALIBERTISTS VERSUS WILLANISTS

Alibert maintained an antagonistic stance toward Willan’s concepts, judging them as contrived. Willanists adhered to Linnaeus’s principles, whilst Alibert, influenced by botanical literature, favored the classification approach proposed by Bernard de Jussieu (1699–1777), a French botanist who grounded his system on numerous visible characteristics. Alibert claimed that skin disorders could only be identified once their full manifestation was witnessed in patients, rather than relying on a singular criterion as executed by Willan at the dispensary. In 1829, Alibert physically represented his thoughts by creating a paradigmatic botanical taxonomy of skin illnesses, known as the Tree of Dermatoses, which was derived from Torti’s Tree of Fevers. Alibert’s depiction of skin illnesses aimed to illustrate the inherent relationships among cutaneous efflorescences in opposition to the Willanist framework, which he deemed artificial. From a clinical, and methodological standpoint, all dermatologists nowadays are Willanists.[6]

ETERNAL REST

Since he had hemoptysis, he moved to a house on Craven Hill in June 1811. He left that year for Funchal, Portugal, in October. At the age of 54, he died there on April 7, 1812. Before his demise, Willan emphatically expressed that his corpse should not be transported to England for burial.[2,5]

POSTHUMOUS WORKS

His protégé Thomas Bateman successfully completed Willan’s Cutaneous Diseases in 1817, further solidifying his mentor’s legacy. The four orders (the pustulae, vesiculae, tubercula, and maculae) that Willan had not completed were included in Bateman’s Delineations of cutaneous diseases, exhibiting the hallmark appearances of the principal genera and species, which also included illustrated plates from Willan’s watercolor drawings.[5]

Willan’s essay “A List of the Ancient Words at Present Used in the Mountainous District of the West Riding of Yorkshire” was published posthumously.[2]

In the churchyard of Hillington, Middlesex, England, there stands a memorial to Willan, perhaps built by his wife.[2]

CONCLUSION

Robert Willan is a unique figure in humanity, ascending from a Quaker to become a legendary authority in dermatology by his unwavering dedication and astute observation. His contributions to the discipline of dermatology will resonate indefinitely. His compassion and empathy for the impoverished compel us to reaffirm our Hippocratic pledge to serve the populace with the highest moral integrity.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required, as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Robert Willan. Wellcome collection. (n.d.), Available from: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/gkpbumh6 [Last accessed on 2024 Nov 15]

- [Google Scholar]

- Robert Willan: Pioneer in morphology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:125-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Willan--a versatile physician and scholar. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:908.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Willan-Dermatologist and humanist extraordinaire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Willan and the French Willanists. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1122-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The dermatology and syphilography of the nineteenth century New York: Praeger; 1981.

- [Google Scholar]

- An eye for an eye . . . (Exodus xxi:23,24) J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:893-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]