Translate this page into:

Lifestyle interventions in dermatology

*Corresponding author: Hima Gopinath, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Mangalagiri, Andhra Pradesh, India. hima36@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gopinath H. Lifestyle interventions in dermatology. CosmoDerma. 2023;3:189. doi: 10.25259/CSDM_234_2023

Abstract

Chronic inflammatory skin disorders such as hidradenitis suppurativa and psoriasis are associated with cardiovascular disease. Lifestyle medicine is a vast and evolving domain that can reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Lifestyle interventions such as exercise, sleep, stress management, nutrition, and mind-body approaches benefit several skin disorders. This review addresses lifestyle interventions that can influence the general health and outcome of patients’ skin disorders.

Keywords

Lifestyle interventions

Psoriasis treatment

Exercise skin

Hidradenitis suppurativa treatment

Mindfulness meditation

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the major contributor to global mortality. Patients with psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa are at a higher risk for cardiovascular disease.[1] Several skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, early-onset androgenetic alopecia, acanthosis nigricans, and acrochordons have also been associated with metabolic syndrome or its components.[2] Cardiovascular disease has low overall heritability. Lifestyle and environment strongly influence cardiovascular disease. Improving lifestyle and managing modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease can prevent more than 80% of cardiovascular events. The Americans Heart Association Life’s Essential 8 contains key measures on eight metrics influencing cardiovascular health. These include diet, physical activity, quitting nicotine, body mass index (BMI), managing blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure, and the newly added metric of sleep.[3] Environmental, economic factors, education, health access, and social and community relationships can influence cardiovascular disease. Psychosocial stress from these domains can promote pathways of chronic inflammation.[4] Systemic and psychosocial aspects of skin disease are often neglected in routine dermatology consultations.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS

Diet

Most data on diet is from epidemiological studies. Thus, there is a dearth of robust data on the ideal diet.[5] The widely recommended DASH (dietary approaches to stop hypertension) eating plan focuses on increasing vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, whole grains, and low-fat dairy while reducing the intake of sodium, red or processed meat, and sweetened beverages.[3]

Exercise

Most individuals do not meet the recommended physical activity and exercise goals. Adults need aerobic physical activity of at least 150 min (moderate) or 75 min (vigorous) and a minimum of two days of muscle strengthening per week. Children above five and adolescents need a higher 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic physical activity with at least three days of vigorous activity and activities to strengthen bones and muscles. Exercise can delay osteoporosis and reduce related fractures. Any physical activity is better than no activity. Physical activity is beneficial in reducing all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, obesity, anxiety, and depression and improving sleep and cognitive performance.[6] Regular exercise slows skin aging, may prevent psoriasis, and improves skin ulcers.[7] Providing a written prescription for exercise instead of verbal instruction is more beneficial in bringing change. It should include all components of exercise-aerobic exercise, strength training, balance, and flexibility. Yoga improves both balance and flexibility. Moderate exercise increases antioxidant enzymes. However, intense and prolonged exercise is detrimental due to increased oxidative stress.[5]

Sleep

People need seven to nine hours of sleep. Longer or shorter durations may be detrimental. Poor sleep is prevalent among all age groups. Sleep duration, quality, regularity, and sleep disorders are all associated with cardiovascular health.[3] Multicomponent cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is a strongly recommended behavioral and psychological intervention in patients with chronic insomnia. It combines cognitive therapy strategies, education on sleep regulation, stimulus control, sleep restriction, sleep hygiene education, relaxation therapy, and other counter-arousal methods.[8]

Substance use

Nicotine exposure from traditional combustible forms and inhaled nicotine delivery systems such as e-cigarettes and secondhand smoke are to be avoided.[3] Smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug use are linked to several skin disorders.[9]

Obesity

The BMI is not a perfect predictor of cardiovascular health. However, a BMI of 18.5–24.9 is recommended. Asians and Pacific islanders have higher risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[3]

MIND-BODY INTERVENTIONS

Brain-mind-heart-body interactions negatively or positively impact cardiovascular health through direct or indirect mechanisms.[10] Common skin disorders such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, acne, and rosacea share common psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, and suicidality. Shared pathomechanisms need to be addressed with multidisciplinary pharmacological and non-pharmacological lifestyle interventions.[11] Psychodermatology liaison clinics can ensure holistic management of skin diseases. For example, cognitive behavior therapy with habit reversal or acceptance and commitment therapy are integral along with pharmacological interventions in body-focused repetitive behaviors such as skin picking disorder.[12] Psychosocial outcomes and even the severity of some skin diseases improve with mind-body interventions such as meditation, biofeedback, hypnosis, and guided imagery. The skin, immune, endocrine, and neural systems are intricately linked. Stress increases inflammation, suppresses immunity, and impedes skin barrier function and wound healing.[13] Mindfulness meditation has received the most research attention. It has its origins in Buddhist meditation practices. It involves moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness. Meditation may improve attention control, emotion regulation, and self-awareness leading to better self-regulation. Neuroscience research is exploring meditation’s positive effects on mental health, physical health, and cognitive performance.[14] Thus, the potential benefits of mind-body interventions and low-risk profile may make them necessary adjuncts in lifestyle interventions

SKIN DISORDERS REQUIRING LIFESTYLE RECOMMENDATIONS

Psoriasis

An unhealthy lifestyle in psoriasis is associated with poorer outcomes. However, the dermatology curriculum does not adequately address health promotion and evidence-based lifestyle interventions for psoriasis.[15] Recent guidelines address cardiovascular risk assessment, regular screening for risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, referrals for risk management, nicotine and alcohol dependence, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in psoriasis patients with varying strengths of recommendation.[16] Dietary intervention (strict caloric restriction) has been reported to cause a 75 % or more reduction in psoriasis area severity index (PASI). However, the quality of evidence is low as the risk ratio was 1.66 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07 to 2.58) in two trials with 323 individuals. However, combining dietary intervention and exercise has moderate quality evidence for psoriasis.[17] A life course approach (based on Life Course Research) that incorporates theoretical models and pathways that link the varied exposures across the life course may be critical for chronic inflammatory disorders such as psoriasis. This long-term approach helps in identifying both risk factors for disease development and a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the disease on the life course.[18]

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with systemic inflammation, obesity, and metabolic and cardiovascular complications. Bariatric surgery has been reported to cause remission in some patients, who were refractory to pharmacological interventions. Weight reduction is strongly recommended in obese patients, as it may reduce disease severity and even lead to disease remission.[19,20] Non-obese patients had better remissions than obese patients (45% vs. 23%), and non-smokers had better remissions than active smokers (40% vs. 29%) in a study that followed up hidradenitis patients over a range of 12–32 years.[21] Patients benefit from referrals for smoking cessation and management of insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Support groups can reduce the feelings of loneliness and social isolation these patients face. Brewers yeast elimination diet has been reported to be helpful in a few studies with small sample sizes. Although the Mediterranean has been reported to be beneficial in a small cross-sectional study, dietary interventions must be explored in studies with large sample sizes and rigorous methodology. Sweat, heat, humidity, and friction can worsen hidradenitis. Loose cotton clothes are preferable.[20]

Acne

In a systematic review, high carbohydrate intake, high glycemic load, and index intake were reported to have a modest pro-acne effect. Dairy can worsen acne in some populations that follow a Western diet.[22] A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies (23,046 acne cases and 55,483 controls) reported a pooled odds ratio of 1.25 (95% CI 1.15–1.36) for any dairy intake.[23] In addition, multiple lifestyle factors such as pollution, tobacco and cannabis, ultraviolet radiation, excessive light exposure from modern gadgets, stress, emotions, and sleep deprivation can affect acne.[24]

Others

Early-life sunburns are associated with melanoma. A higher cumulative sun exposure is associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Consuming more vegetables and fruits may reduce the risk of skin cancers whereas a high intake of meats and fats may increase the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. Lifestyle interventions are being explored in atopic dermatitis.[9,25] Aging is associated with chronic low-level inflammation called “inflammaging.” Factors in the exposome such as ultraviolet radiation, smoking, pollution, and diet can also influence inflammaging in the skin.[26] High sugar intake and cooking methods such as grilling, frying, and roasting may accelerate skin aging.[9] Thus, several skin disorders are influenced by lifestyle.

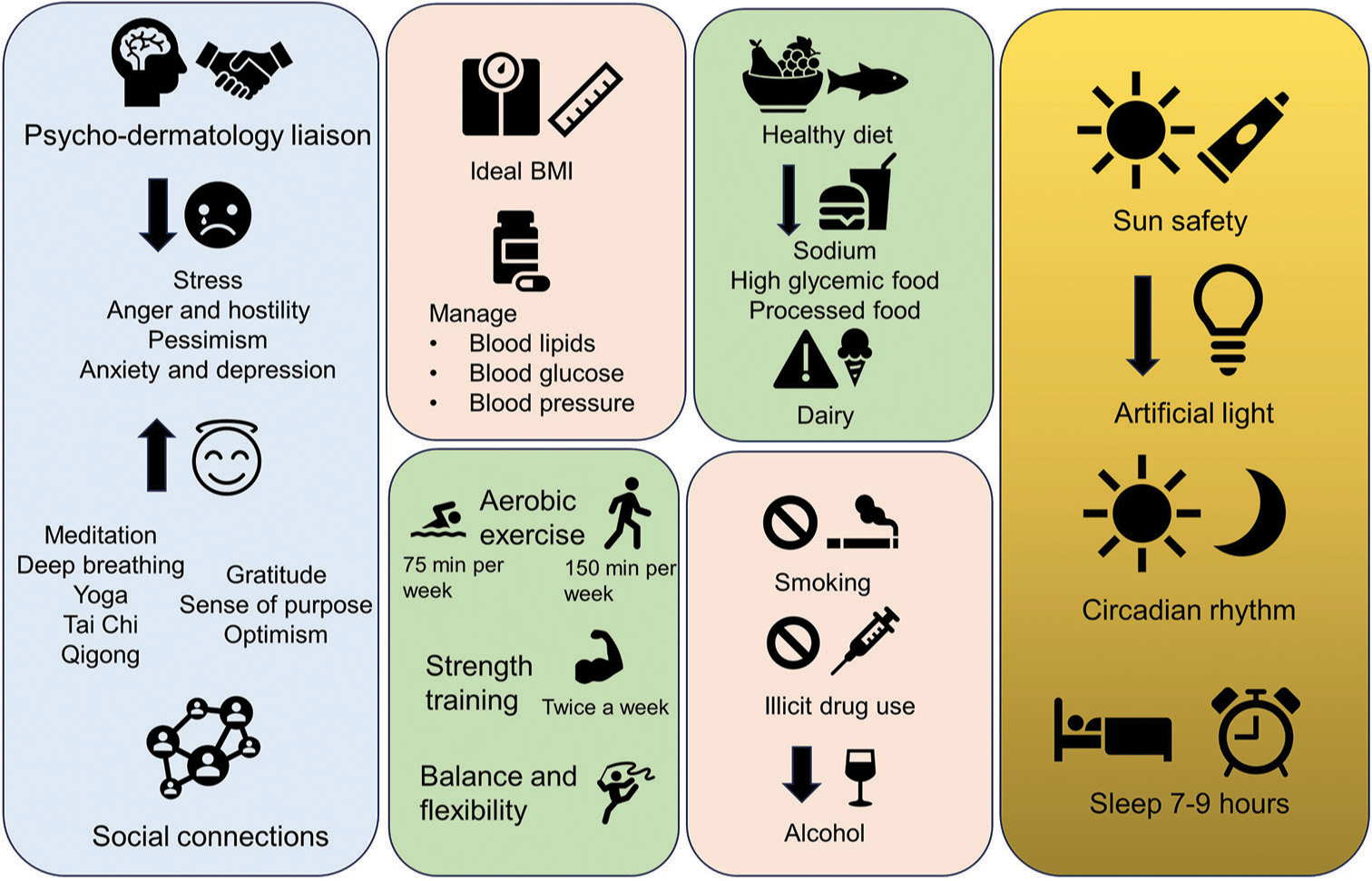

Dermatologists can play an integral role in health promotion [Figure 1].[3,5,6,10,24,27,28] Training in collaborative patient-centered communication skills will help dermatologists change patient behavior. Personal, social, economic, and cultural factors can influence patient response.[25] Digital interventions are increasingly used to promote, assist, and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Diet and physical activity are the most popular domains in digital interventions. Websites, smartphone applications, social media-based interventions, image-based devices, wearable gadgets, and personal digital assistant devices can improve health access, lower cost, and enable better data collection with high user acceptability. However, it is essential to ensure that digital interventions are evidence based.[29]

- Lifestyle interventions in dermatology.

CONCLUSION

Dermatologists can identify several systemic ailments with a glance at the skin. Providing holistic management that considers the systemic associations and psychosocial impact of skin diseases is essential. Increased awareness, training, and research on lifestyle interventions in skin diseases are needed. Adding lifestyle interventions to our dermatology prescriptions is the need of the hour.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Chronic Systemic inflammatory skin disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46:100799.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin and metabolic syndrome: An evidence based comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:302-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- From seven sweethearts to life begins at eight thirty: A journey from life's simple 7 to Life's essential 8 and beyond. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e027658.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Integrative dermatology for psoriasis: Facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:93-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336656/9789240015128-eng.pdf Available fom: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336656/9789240015128-eng.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Exercise in dermatology: Exercise's influence on skin aging, skin cancer, psoriasis, venous ulcers, and androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:183-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: An American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17:255-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holistic dermatology: An evidence-based review of modifiable lifestyle factor associations with dermatologic disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:868-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Life's essential 8: Updating and enhancing the American heart association's construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18-43.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The mind body connection in dermatologic conditions: A literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:628-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychodermatology of skin picking (excoriation disorder): A comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13661.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stress and skin: An overview of mind body therapies as a treatment strategy in dermatology. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:e2021091.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:213-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Providing lifestyle behaviour change support for patients with psoriasis: An assessment of the existing training competencies across medical and nursing health professionals. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:602-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-113.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifestyle changes for treating psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD011972.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Non-pharmacologic approaches for hidradenitis suppurativa-a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:11-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: A cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dairy intake and acne vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 78,529 Children, adolescents, and young adults. Nutrients. 2018;1049

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The influence of exposome on acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:812-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifestyle intervention should be an essential component of medical care for skin disease: A challenging task. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:934-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inflammaging and the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1087-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circadian rhythm and the skin: A review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12:42-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mind-body practices for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Investig Med. 2013;61:827-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial: Using technology for healthy lifestyle and weight management. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:973006.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]