Translate this page into:

Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma

*Corresponding author: Dr. Jagjeet Sethi, Department of Dermatology, Aesthetics and Lasers, Hope Clinic, Shillong, Meghalaya, India. jagjeetsethi@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Syiemlieh A, Sethi JK. Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma. CosmoDerma. 2025;5:5. doi: 10.25259/CSDM_184_2024

Abstract

Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma (PSEK) is the rarer type of erythrokeratoderma and is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition. The other more common form is erythrokeratoderma variabilis (EKV). Although these conditions vary clinically, their similarity in histopathology and likelihood of similar genetic origins have made the conditions be considered one entity called EKV et progressiva. We report a case of PSEK treated with isotretinoin and oral vitamin A capsules in the isotretinoin “drug holiday” period.

Keywords

Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma

Erythrokeratoderma

Isotretinoin

Oral vitamin A

Drug holiday

INTRODUCTION

Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma (PSEK), earlier known by the name of Darier– Gottron syndrome, after Darier and Gottron, who each described the condition in 1911 and 1923, respectively. It is one of the types of erythrokeratoderma, which are genodermatoses having abnormal keratinization. Erythrokeratoderma is of two types, erythrokeratoderma variabilis (EKV) and progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma (PSEK). Since it is a genetically inherited disorder, it has been assigned the on-line Mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM) numbers, OMIM 133200 for EKV and OMIM 602036 for PSEK. PSEK is the rarer one of the two erythrokeratoderma.[1] These may also have syndromic associations like keratitis, ichthyosis, deafness syndrome, and hystrix-like ichthyosis with deafness syndrome. Here, we report a case of PSEK in a 12-year-old girl with no family history who was treated with isotretinoin and oral vitamin A capsules in the isotretinoin “drug holiday” period to avoid the skeletal side effects of isotretinoin.

CASE REPORT

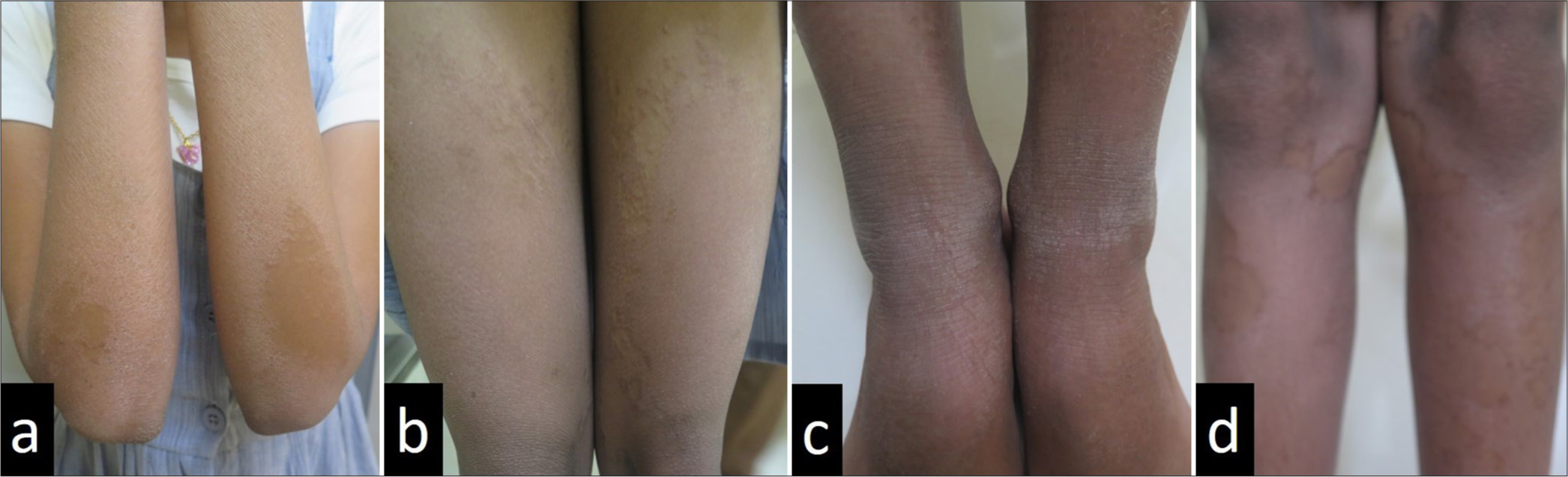

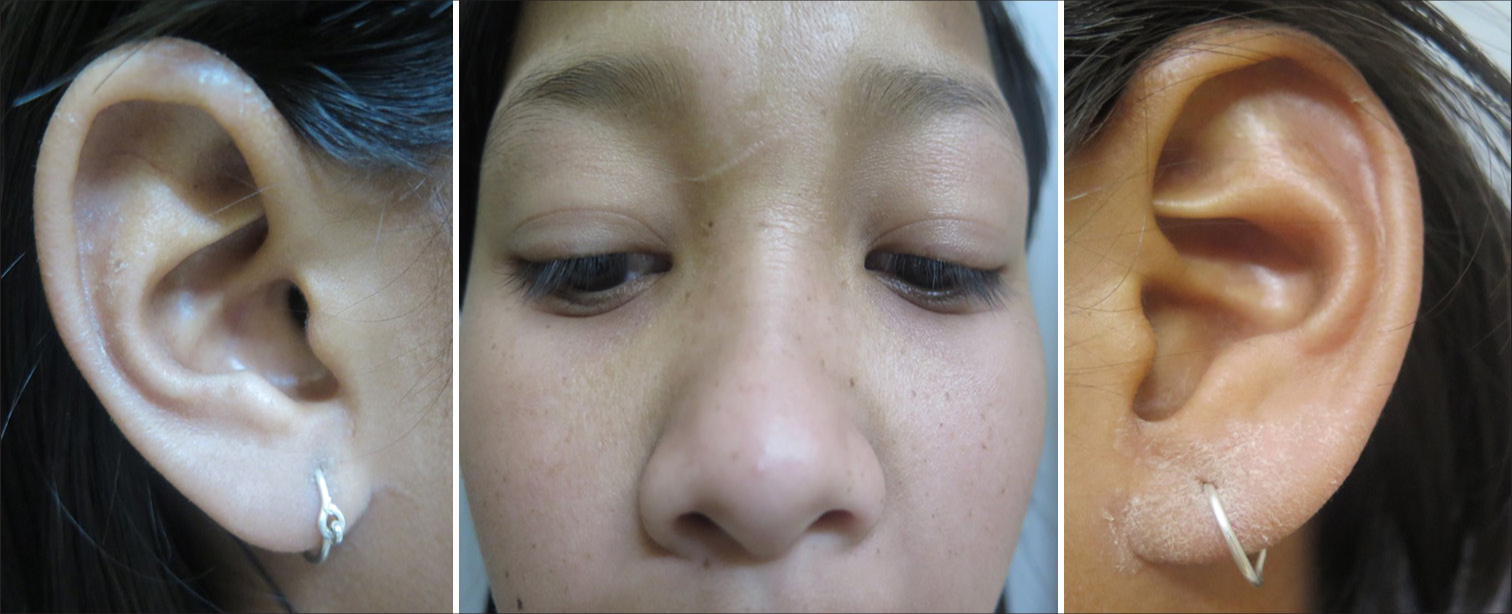

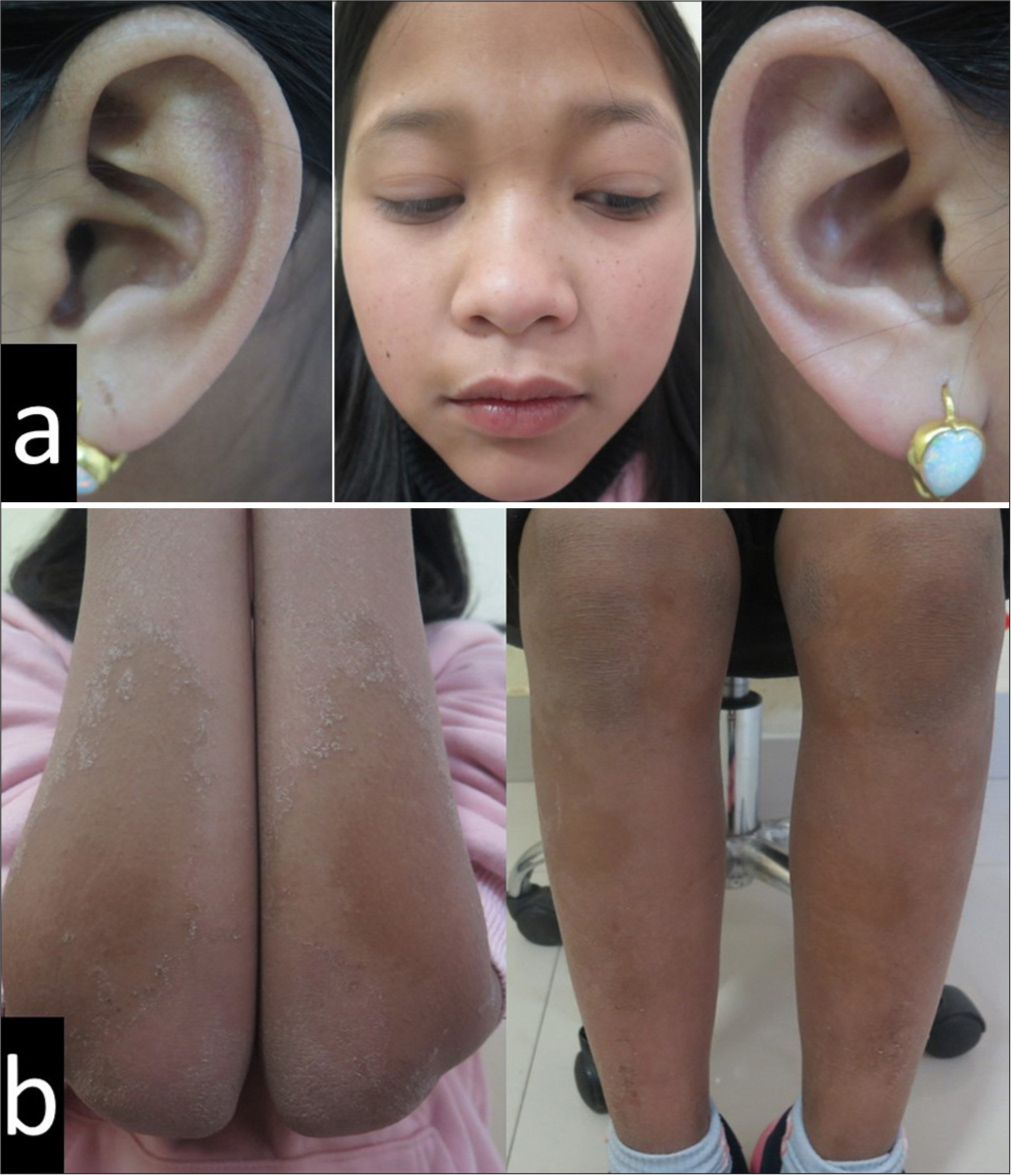

A 12-year-old girl presented to us with dryness of arms and legs since the age of four years with thickening and flaking of the skin over her hands, elbows, ankles, and knees. The lesions were asymptomatic with no similar family history. She was born out of a non-consanguineous marriage and neither she nor her family members had any co-morbidities. On cutaneous examination, she had striking bilaterally symmetrical thin erythematous and keratotic plaques with peripheral scaling over both extensor lower limbs and knees, extensor forearms, and elbows [Figure 1a-d] with obvious symmetrical involvement of the face and ear lobes [Figure 2]. Her oral mucosa, genitals, hair, and nail examination were within normal limits. We considered PSEK, EKV, pityriasis rubra pilaris as our differentials. On investigating her hemogram, her hemoglobin was 10.9 g/dL, while the rest was normal. We proceeded with a biopsy of the periphery of the plaque on her right leg and it showed [Figure 3a] irregular psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with [Figure 3b] orthokeratosis and foci of parakeratosis, slight hypergranulosis, and sparse superficial perivascular infiltrate and was diagnosed with erythrokeratoderma. Due to financial constraints with capsule acitretin, she was started on oral isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg and continued for six months with topical emollients, 12% ammonium lactate lotion once daily with good improvement of the face [Figure 4a], which had returned to normalcy, but the forearm and leg plaques had begun showing signs of winter exacerbation [Figure 4b]. Considering the possible skeletal side effects of isotretinoin, we moved over to oral vitamin A at a dose of 50,000 U/day, for a “drug holiday.” After about four months of being on oral vitamin A, the patient showed a response of the limb lesions and no recurrence of the facial lesions [Figure 5]. Since the patient had persistent lesions, we stopped her oral vitamin A after four months, restarted her on isotretinoin, and continued till six months with some satisfactory results on the upper limbs but not the lower limbs [Figure 6]. While on treatment, the patient did not have any complaints suggestive of any side effects from either medication.

- A 12-year-old girl with bilaterally symmetrical thin erythematous and keratotic plaques with peripheral scaling over both extensor (a) upper and (b-d) lower limbs.

- Similar obvious symmetrical involvement of the face and ear lobes can also be seen.

![(a) Irregular psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis and sparse superficial perivascular infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E], ×100), and (b) A clear orthokeratosis of the stratum corneum and foci of parakeratosis, focal hyper-granulosis and sparse dermal lymphocytic infiltrate and dilated papillary dermal capillaries which are suggestive of erythrokeratoderma (H and E, ×400).](/content/130/2025/5/1/img/CSDM-5-5-g003.png)

- (a) Irregular psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis and sparse superficial perivascular infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin [H and E], ×100), and (b) A clear orthokeratosis of the stratum corneum and foci of parakeratosis, focal hyper-granulosis and sparse dermal lymphocytic infiltrate and dilated papillary dermal capillaries which are suggestive of erythrokeratoderma (H and E, ×400).

- After six months of being on oral isotretinoin, there was good improvement of the (a) face with persistence and aggravation of the (b) forearm and leg plaques.

- Then the patient was put on four months of oral vitamin A and showed good response of the limb lesions and no recurrence of the facial lesions.

- Six months after restarting oral isotretinoin, patient can be seen to have satisfactory results on the upper limbs, but not the lower limbs.

DISCUSSION

Clinically, PSEK has well-defined erythematous and keratotic plaques present predominantly over the extensor aspect of the extremities, including buttocks and elbows. There is a high incidence of involvement of the face, sometimes with palms and soles. The trunk is usually spared. They are active and slowly progressive in childhood and stabilize by adulthood. A prior history suggestive of harlequin ichthyosis may be helpful as reported recently in a newborn with harlequin ichthyosis and severe thrombocytopenia who gradually progressed into PSEK.[2]

EKV, previously known as Mendes de Costa Syndrome, is also a symmetrical keratoderma involving the trunk, both the flexor and extensor aspects of the extremities, and almost always spares the face. The lesions are often described to be of two forms and are usually co-existent with one form predominating the other. The initial signs are usually transient migrating erythematous patches in geographic or annular distribution which last a few minutes, hours to days. The erythema is usually either accompanied or followed by keratotic plaques in the same pattern of involvement.[1] Despite being clinically different, they are indistinguishable histopathologically. In addition, while many report that cold temperature aggravates both conditions, the hypothesis that more than PSEK, EKV is triggered by temperature, ultraviolet, sun exposure, and emotional stress has been stated.[3]

Both conditions are inherited as autosomal dominant, while some autosomal recessive inheritance and sporadic cases have been reported in PSEK. The genes for EKV have been found to be connexin protein-encoding genes, GJB3 or GJB4, and occasionally GJA1. These code for connexin 31, connexin 30.3, and connexin 4, respectively. The function of the proteins is the formation of the hexameric gap junctions which mediate intercellular transport, communication, and metabolism.[4] This therefore affects intercellular cohesion and causes communication errors resulting in hyper-keratinization. Although no gene has ever been found in PSEK, in 2006, only the locus was found on chromosome 21q11.2–21q21.2 in a Chinese family with PSEK.[1] Then, a study found a loricrin-encoding gene abnormality in PSEK resulting in abnormal loricrin accumulation in the nucleus of keratinocytes leading to abnormal keratinization.[4] Interestingly, Van Steelsel et al.[5] found the gap junction gene GJB4 to be the implicated abnormal gene in their case of PSEK, which is also the gene, which has been known to cause EKV. This led to some authors proposing the term EKV et progressiva, which clubs the two different types of erythrokeratoderma into one entity. This suggestion also comes from a case report by Macfarlane et al.[6] where two sisters from the same family had each of the types, suggesting that they may be varied presentations of one disorder spectrum.

On cutaneous biopsy of the lesion, there is orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with acanthosis and papillomatoses in more verrucous lesions. There is usually hypergranulosis with some dilated papillary dermal capillaries and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.[3]

The treatment approach for both conditions is relatively similar. For milder and more localized lesions, the approach is usually topical applications which always include an emollient and may vary from keratolytics like salicylic acid and urea to retinoids such as tretinoin or tazarotene and calcipotriol. Topical steroids have also been shown to give a response in the erythematous patches of EKV, which do not respond to retinoids. The retinoids work in more keratotic lesions of EKV and PSEK.[7] For diffuse involvement, adding oral retinoids such as isotretinoin, etretinate, and acitretin with or without phototherapy has been tried.

The oral retinoids are usually isotretinoin, acitretin, and etretinate. The half-life of etretinate is up to 120 days and can be detected in the blood even up to three years. Acitretin, its metabolite, becomes undetectable in 3–4 weeks with a half-life of two days. However, on consuming with ethanol, acitretin is converted to etretinate and thus requires three years of contraception to avoid pregnancy post-treatment. Acitretin is often preferred to isotretinoin because of its better effect on palms and soles hyperkeratosis than isotretinoin. However, in women of the reproductive age group, isotretinoin is still the option of choice in view of its short half-life and the ability to take “drug holidays.”[8] Such drug holidays are usually preferred in periods of remission. The dose required is often under 1 mg/kg of isotretinoin and <0.5 mg/kg of acitretin.

Since retinoids can affect epiphysial fusion, it is often preferred to delay treatment if possible. Apart from the short-term side effects of cheilitis, eye irritation, and mucositis, it can also cause spurs and hyperostosis in the spine known as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, and even ligament and tendon ossification at the joints. There are also, however, patients being on systemic retinoids for decades with no systemic side effects also being reported.[9] The alternate approach to treatment has been the use of oral vitamin A up to the dose of 80,000 U/day safely reported in a 15-year-old.[10] Since our patient had already been on six months of isotretinoin, we wanted to put her on isotretinoin drug holiday, but still on oral vitamin A since she was not completely cleared of her symptoms.

CONCLUSION

We wanted to bring forth our case of PSEK because of its rarity. A quick PubMed search reveals <100 cases reported globally so far. This clearly warrants more reporting for a better understanding of the disorder.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Erythrokeratodermas: A classification in a state of flux? Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:127-141. quiz 142

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma manifesting as harlequin-like ichthyosis with severe thrombocytopenia secondary to a homozygous 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase mutation. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;14:55-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma associated with punctate palmoplantarkeratoderma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:183-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma: Report of a Turkish family and evaluation for loricrin and conexin gene mutations. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:582-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The missense mutation G12D in connexin30.3 can cause both erythrokeratodermiavariablis of Mendes da Costa and progressive erythrokeratodermia of Gottron. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:657-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is erythrokeratoderma one disorder? A clinical and ultrastructural study of two siblings. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:487-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erythrokeratoderma variabilis: Case report and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:180-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral retinoid therapy for disorders of keratinization: Single-centre retrospective 25 years' experience on 23 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:267-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: A follow-up of 23 years of use of systemic retinoids. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 Suppl 1):S72-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case of erythrokeratodermia variabilis successfully treated with oral vitamin A. J Dermatol. 2015;42:1124-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]