Translate this page into:

P16 immunohistochemistry is an easy and cheap alternative to in situ hybridization to detect human papillomavirus-induced squamous cell carcinoma

*Corresponding author: Pradeep S. Nair, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Government Medical College, Trivandrum, Kerala, India. dvmchtvm@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Nair PS, Sudhesan A. P16 immunohistochemistry is an easy and cheap alternative to in situ hybridization to detect human papillomavirus-induced squamous cell carcinoma. CosmoDerma. 2024;4:12. doi: 10.25259/CSDM_256_2023

Dear Sir,

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common cutaneous malignancy after basal cell carcinoma. Ultraviolet radiation is the most important risk factor for SCC followed by genetic and phenotypic risk factors. Human papillomavirus (HPV), type 16, 18, 31, and 33, is another risk factor for anogenital and oropharyngeal SCC. It is difficult and complicated to detect the HPV in SCC induced by it. The P16 is a tumor suppressor protein, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, with the gene located at chromosome 9p21.[1] High positivity of this protein in SCC is a strong marker for HPV infection and can be alternatively used to diagnose HPV-induced SCC without going for HPV in situ hybridization or DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with sufficient accuracy.[1] The P16 positivity also has prognostic significance.

A 50-year-old male with multiple homosexual contacts, passive partner, peno-anal contacts with known partners presented with a well-defined plaque on the perianal region of an 8-month duration. The patient denied a previous history of verrucous lesions on the perianal region. On examination, there was a well-defined skin colored erythematous firm plaque of 7 × 4 cm with everted edges at the perianal region extending to the intergluteal cleft and a small ulcer of 2 × 3 cm with everted edges and floor covered by necrotic slough at the right mid region of the plaque [Figure 1].

- Well-defined firm plaque with ulceration at the perianal region.

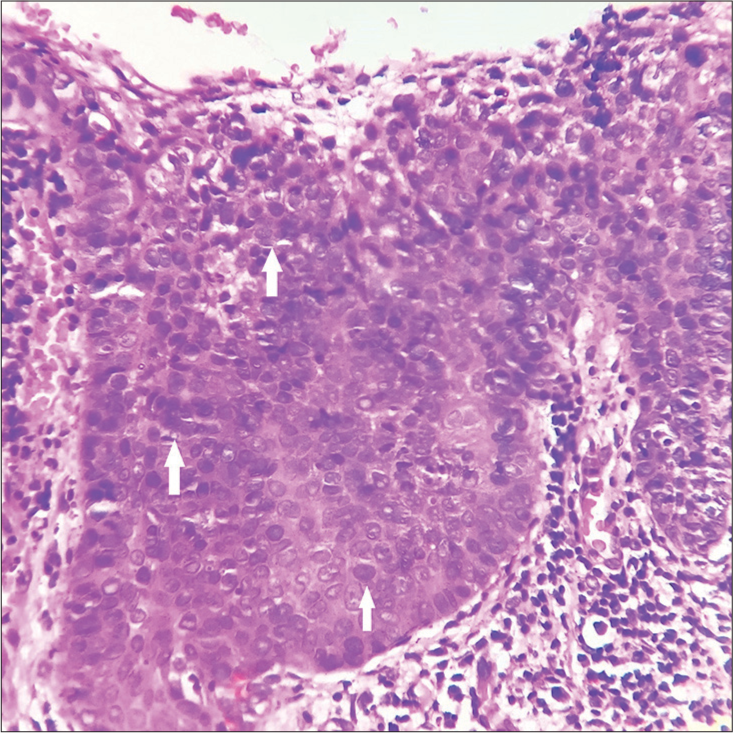

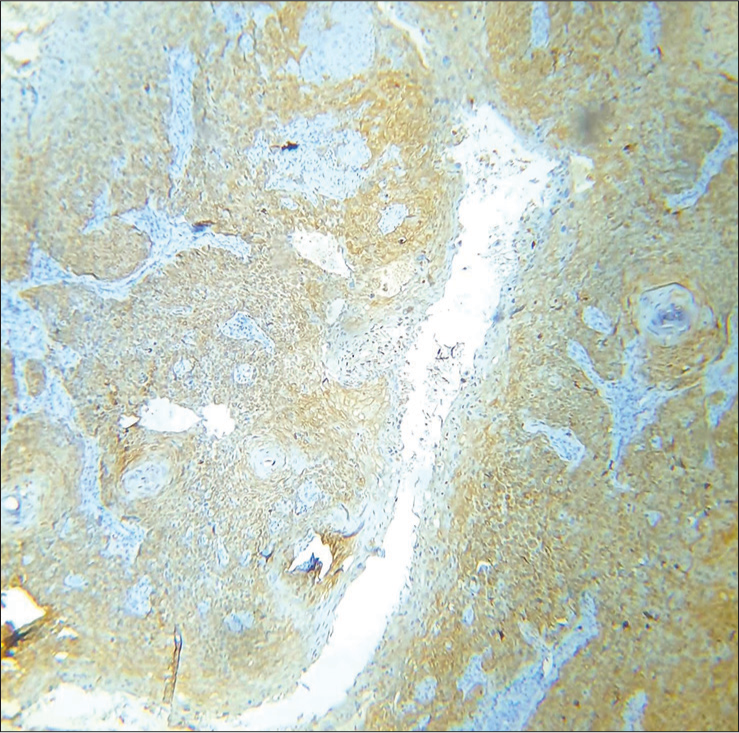

Blood hemograms, liver function tests, and renal function tests were normal. Viral markers for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C were negative. The venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and treponema pallidum hemagglutinaton assay (TPHA) were non-reactive. A skin biopsy from the plaque showed an ulcerated acanthotic epidermis with squamous proliferation and dense infiltrate in the dermis [Figure 2]. High power showed full-thickness dysplasia with atypical squamous cells with moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The dermis showed dense lymphoid infiltrate. No invasion into the dermis was seen in the sections. All these were suggestive of SCC in situ [Figure 3]. A p16 immunohistochemistry showed strong positivity in the epidermis suggestive of HPV-induced SCC [Figure 4]. The patient was referred to surgery for excision. During follow-up after one year of excision, there was no further recurrence.

- Acanthotic epidermis with proliferation of squamous cells, H and E ×40.

- Skin biopsy (high power) showing epidermal ulceration with dysplastic atypical squamous cells (arrows), H and E ×400.

- Immunohistochemistry showing strong positivity for p16 in the epidermis, immunohistochemistry ×400.

Our patient gave a history of multiple homosexual contacts but denied any history of verrucous lesions on the perianal region suggestive of condyloma acuminata. However, it is possible that the patient must have missed noticing any such lesions in the perianal region or the lesions could have been intra-anal or rectal. Skin biopsy was consistent with SCC in situ, and a strong p16 positivity indicates this to be HPV-induced SCC of the perianal region. The oncogenic strains of HPV can induce SCC in the genitals, anal, perianal, and oropharyngeal areas. The most oncogenic is HPV 16. The gold standard to detect HPV in skin biopsy specimens in cases of SCC is in situ hybridization or DNA PCR, which are highly complicated, expensive, and not available in most laboratories. Alternately, p16 immunohistochemistry is cost effective and easily available in most laboratories, has sufficient sensitivity and specificity, and is a strong marker for HPV-induced SCC.[2] The SCC following premalignant dermatosis and chronic non-healing ulcers have a bad prognosis and a greater chance of metastasis compared to HPV-induced SCC. The HPV-induced SCC is usually well differentiated and usually does not metastasis. Ths is the clinical significance for doing p16 immunohistochemistry in cases of SCC.[3] The HPV-induced SCC may not require wide excision, nor frequent follow-up compared to SCC induced by the other aforementioned causes. Most studies regarding p16 have been done in oropharyngeal carcinomas, but it is also useful in anogenital SCC as the present report shows.[4] There are also studies showing that p16-positive SCC has a better prognosis than p16-negative SCC.[5] We are reporting that p16 immunohistochemistry is a cheap, easily available, and effective method to detect HPV-induced SCC rather than going in for in situ hybridization or DNA PCR.

Ethical approval

Institutional review board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Clinicopathological features of anal and perianal and their relationship to Human papilloma virus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:827-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is the improved prognosis of p16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma dependent of the treatment modality? Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1256-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distinctive risk factor profiles for Human papilloma virus-16 and Human papilloma virus-16 negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary tumor volume and prognosis for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17:107-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic implications of p16 and HPV discordance in oropharyngeal cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): A multicentre, multinational individual patient data analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:239-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]